Making Peace in Jerusalem

What are some of your hopes for Jerusalem?

David Arnow

Jewish

David Arnow

Jewish

The Dome of the Rock, Islam’s third holiest site, rests on the very spot where the Second Temple stood. The Church of the Holy Sepulcher lies a stone’s throw away. Such a concentration of holiness creates two possibilities. Jerusalem will either ignite an explosion that will turn the world upside down. Or Jerusalem will teach us how to live in peace. Visitors to the Western Wall in Jerusalem, a retaining wall for the Second Temple, often write important notes and insert them into crevices in the Wall. If God did so, the note might say: “O, Jerusalem, holy city, you have seen enough blood. Let my children finally grant you peace.” We are all created in God’s image. We pray to the same God. God doesn’t want us to kill one another—over Jerusalem, or anything else.

Related Texts

Pray for the peace of Jerusalem. May those who love you be at peace. May there be peace within your ramparts, serenity in your citadels…. If I forget you Jerusalem, let my right hand wither, let my tongue stick to my palate if I cease to think of you, if I do not keep Jerusalem in memory even at my happiest hour.

— Psalms 122:6-7 and 137:5

My heart’s in the east and I languish on the margins of the west. How taste or savor what I eat? How fulfill my vows and pledges while Zion is shackled to Edom and I am fettered to Arabia? I’d gladly give up all the luxuries of Spain if only to see the dust and rubble of the Shrine.

— Judah Halevi (c. 1075-1141), My Heart’s in the East

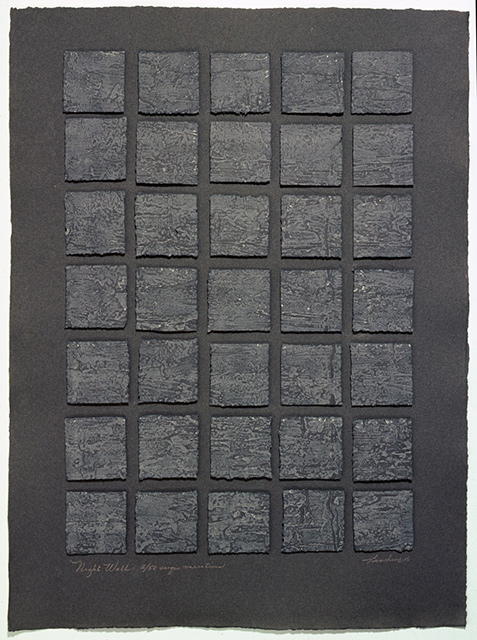

For your name scorches the lips

Like the kiss of a seraph

If I forget you, Jerusalem,

Which is all gold . . .

Jerusalem of gold, and of bronze, and of light

Behold I am a violin for all your songs.

— Naomi Shemer (1930-2004), Jerusalem of Gold*

Mary C. Boys

Christian

Mary C. Boys

Christian

Jerusalem, it has been said, is not a single city but a multitude of cities “built over the same spot, operating at the same moment, and contending for hegemony.”* And within that multitude of cities dwell adherents of the world’s monotheistic religions, living on top of one another—and too often striving with each other. One hopes for religious leaders audacious enough to advance interreligious dialogue. One hopes as well for a thriving Christian community engaged in the imperative of peace-making and interreligious/inter-cultural dialogue.

Related Texts

For Christians, the Holy Land is not simply an illustrious chapter in the Christian past. As Jerome wrote to his friend Paula in Rome urging her to come and live in the Holy Land, “the whole mystery of our faith is native to this country and city. Nothing else in Christian experience can make this claim; nothing has such fixity. No matter how many centuries have passed, no matter where the Christian religion has set down roots, Christians are wedded to the land that gave birth to Christ and the Christian religion.

— Robert Wilken, The Land Called Holy: Palestine in Christian History and Thought (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1992), 254

Then I saw a new heaven and a new earth, for the first heaven and the first earth had passed away, and the sea was no more. And I saw the holy city, the New Jerusalem, coming down out of heaven from God, prepared as a bride adorned for her husband. And I heard a loud voice from the throne, saying, “See, the home of God is among mortals. He will dwell with them; they will be his peoples, and God himself will be with them, he will wipe every tear from their eyes.”

— Revelation 21:1-4

The land of Israel has always been of central significance to the Jewish people. However, Christian theology charged that the Jews had condemned themselves to homelessness by rejecting God’s Messiah. Such supersessionism precluded any possibility for Christian understanding of Jewish attachment to the land of Israel. Christian theologians can no longer avoid this crucial issue, especially in light of the complex and persistent conflict over the land. Recognizing that both Israelis and Palestinians have the right to live in peace and security in a homeland of their own, we call for efforts that contribute to a just peace among all the peoples in the region.

— Excerpt from “A Sacred Obligation,” 2002 by the Christian Scholars Group on Christian-Jewish Relations

Muhammad Shafiq

Muslim

Muhammad Shafiq

Muslim

Jerusalem is an Abrahamic city, sacred to Muslims, Christians and Jews. To Muslims, it is called al Quds – noble, sacred, or Bait al Maqdas – a sacred house or place. Our hopes are that interfaith dialogue will take root in Jerusalem to bring peace and harmony among the Abrahamic people. We hope for lasting peace there through the implementation of a U.N. Resolution to promote peaceful coexistence among the three monotheistic faiths.

Note: Translation of the Qur’anic verses and many of the Hadith translation with references were taken from Islamicity.com; some translations of and references to the Hadith were taken from ahadith.co.uk.

Related Texts

What are some of your hopes for Jerusalem?

Jerusalem is an Abrahamic city, sacred to Muslims, Christians and Jews. To Muslims, it is called al Quds – noble, sacred, or Bait al Maqdas – a sacred house or place. Our hopes are that interfaith dialogue will take root in Jerusalem to bring peace and harmony among the Abrahamic people. We hope for lasting peace there through the implementation of a U.N. Resolution to promote peaceful coexistence among the three monotheistic faiths.

What is the spiritual significance of Jerusalem in our traditions?

- Jerusalem was the original place (Qibla) toward which Muslims turned for their five-times-daily prayer. Some years later Muhammad (peace be upon him) was told to change the Qibla from Jerusalem to Makkah (2:142-144).

- Jerusalem is the home of our Qur’anic and Muslim prophets (peace be upon them). Muslims respect the Biblical prophets including Abraham, Isaac, Ishmael, Jacob, Jesus, Moses, David and Solomon, from whom we learned the Oneness of God.

- Jerusalem is al Quds (noble, sacred) and Al Quddus is one of the attributes of God in Islam. It is an al-ard al-Muqaddasah (the Sacred Land, 5:21) and its surroundings are called Barakna Hawlaha (God blessed its precincts, 17:1).

- Jerusalem is the third holiest city in Islam after the cities of Makkah, Madina.

- Jerusalem is the site of Isra (Muhammad’s night journey from Makkah to Jerusalem) and Mi`raj (Muhammad’s ascension to heaven). The importance of these two events for Muslims is reflected in their reverence for the two sacred places.

- Muslims believe that Jerusalem is the only place on earth where God brought together all prophets during Muhammad’s ascension to heaven and they prayed together and Muhammad was asked to lead them in prayers.

- Al Aqsa in Jerusalem and the Ka`ba in Makkah are the only two mosques mentioned by name in the Qur’an.

- Some great companions of prophet Muhammad are buried in Jerusalem

- Most significant is the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem, a great monument of Muslim architecture.

What are some of your tradition’s myths concerning Jerusalem?

Muhammad’s night journey and ascension into heaven (al-lsra’ and al Mi’raj is significant in Muslim tradition. According to Muslim tradition, Muhammad was transported one night on a winged mule (Burraq) from Mecca (Makkah) to Jerusalem. The archangel Gabriel was riding the mule. According to some narrations, he was welcomed at Jerusalem by all the prophets, including Abraham, Moses and Jesus (peace be upon all of them). After meeting them, Gabriel asked Muhammad to lead the prophets in prayers. Afterwards, Muhammad was brought to the place where the Dome of the Rock is built and ascended to heaven accompanied by Gabriel.

It is said that the top portion of the Rock ascended with Muhammad until he reached heaven and then it returned to its place. Today it sits on the top of the rock like a canopy. There is a mark on the top of the Rock that is said to be Muhammad’s footprint. There is also is a mark of Abraham’s feet on a stone on which, according to Muslim tradition, he stood to build the Ka`ba — the House of God at Makkah. In his ascension, Muhammad passed through the seven heavens where he encountered earlier prophets.

During his ascension to heaven, Muhammad received the command to establish five daily prayers (Salat) that all Muslims must perform. It is said that God first commanded him to worship 50 times a day. When Moses heard about it, he persuaded Muhammad to go back to God to reduce the number. Because of Muhammad’s plea, God reduced it to 10 times. Moses insisted that also was too many and said he must go back to God to further reduce the number. Again at Muhammad’s request, God reduced it to five times a day. He said whoever would pray five times daily would be rewarded as though the person had prayed 50 times. Moses told Muhammad that even five times were too many because his people found it hard to pray just three times a day. Muhammad responded that he hoped the community would fulfill its obligation of five times.

The story of Isra and Miraj is full of wonderful signs and symbols. Muslim scholars, Sufis (mystics) and poets have interpreted it in deep, meaningful ways. There is, however, one essential point: It is an example of every Muslim’s deep devotion and spiritual connection with Jerusalem.

The whole journey happened in a portion of a night, although some critics argue Muhammad’s journey was spiritual and not physical. Like Christians and Muslims who believe that Jesus physically ascended to heaven, most Muslims believe in Muhammad’s physical ascension to the heavens on that night. them for being patient throughout their ordeal. God blessed the Israelites with power and destroyed the Pharaoh and his army (7:137).

What is the spiritual significance of Jerusalem in your tradition?

David Arnow

Jewish

David Arnow

Jewish

Jerusalem’s spiritual importance to Jews and Judaism would be hard to exaggerate. The Bible mentions Jerusalem or Zion, a rough synonym, more than 800 times, while the traditional daily liturgy includes more than 50 such references with Grace after Meals adding 13 more. When Jews pray, we face Jerusalem. Jerusalem’s significance lies not just in the fact that it was ancient Israel’s capital city — and is so again — but because it was the location of the First and Second Temples. From the reign of Solomon, in the 10th century B.C.E., to the destruction of the Second Temple in 70 C.E., these temples stood for almost a thousand years. The Temple was the heart of the Israelite religion, a place of pilgrimage on festivals and the site of sacrificial rites. It may be hard for us to understand today, but throughout the ancient world sacrificial rites provided the primary sense of connection between a people and its gods. In fact, the Hebrew word for “sacrifice” is related to a word that means “to draw close.”

Judaism as we know it today evolved in the wake of the Temple’s destruction. In order to survive, Judaism became portable. Sacred moments in time would substitute for the loss of sacred space. Part of Judaism’s evolution in the post-Temple era involved ritualizing the traumatic sense of loss. Thus four of Judaism’s six traditional fast days commemorate different phases of the Temple’s destruction. When plastering a house some still practice the custom of leaving a portion unplastered as a remembrance of the Temple.[127. Tosefta, Baba Batra 2:17 (second or third century).] At every Jewish wedding, breaking a glass evokes the destruction of the Temple.

At the same time, restoration of Jerusalem and the Temple came to express Judaism’s deepest messianic hopes. The last of the seven nuptial blessings declares, “Soon may there be heard in the cities of Judah and in the streets of Jerusalem, the voice of joy and gladness . . .” And we find similar allusions in the Haggadah. Note the refrain of a beloved Seder song, Adir Hu, which began appearing in Haggadot in the 14th century: “May He build His Temple very soon. O God, build Your Temple speedily.” One of the Seder’s most vivid evocations of the Temple appears in a passage attributed to Rabbi Akiva (first and second centuries C.E.) found in the blessing over the second cup of wine:

. . . So Lord our God and God of our ancestors, enable us to reach also the forthcoming holidays and festivals in peace, rejoicing in the rebuilding of Zion Your city, and joyful at Your service [i.e., the sacrificial service]. There we shall eat of the offerings and Passover sacrifices whose blood will reach to the walls of Your altar for acceptance.

The Haggadah celebrates God’s past redemption of the Israelites from Egypt to sustain hope in God’s ultimate restoration of the Jewish people to a Jerusalem rebuilt, to a city that lives in peace.

Mary C. Boys

Christian

Mary C. Boys

Christian

Above all in Christian memory, Jerusalem is irrevocably linked to Jesus. Although he was from the Galilee and much of his ministry took place in that region, the centripetal role his disciples gave to his passion, death and resurrection—events that took place in Jerusalem—meant that the city figured prominently for them. Then, too, it was in an “upper room” in Jerusalem that the church began (Acts 1:12-14), and in Jerusalem that the first martyr, Stephen, was killed (Acts 7:54-60).

The followers of Jesus went out from Jerusalem into the Mediterranean world and beyond preaching the Gospel. Yet when early Christians elected to retain the Scriptures of the Jews as theirs as well—the “Old Testament”—they shared with Jews the memory of precious sites of biblical geography, especially Jerusalem. Eventually, the holy places Christians venerated became part of a sacred landscape, what they came to call the “holy land.” [79. See Robert L. Wilken, The Land Called Holy: Palestine in Christian History and Thought (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1992).]

Jerusalem is not simply a sacred space in the Christian imagination, but also a symbol of the meeting place between God and God’s people. A poignant illustration is the chant traditionally sung at funerals in the Roman Catholic tradition at the final farewell to the body:

May the Angels lead you into paradise:

may the Martyrs come to welcome you,

and take you to the holy city, Jerusalem

May choirs of Angels welcome you,

and with Lazarus who is poor no longer

may you have eternal rest.

Muhammad Shafiq

Muslim

Muhammad Shafiq

Muslim

- Jerusalem was the original place (Qibla) toward which Muslims turned for their five-times-daily prayer. Some years later Muhammad (peace be upon him) was told to change the Qibla from Jerusalem to Makkah (2:142-144).

- Jerusalem is the home of our Qur’anic and Muslim prophets (peace be upon them). Muslims respect the Biblical prophets including Abraham, Isaac, Ishmael, Jacob, Jesus, Moses, David and Solomon, from whom we learned the Oneness of God.

- Jerusalem is al Quds (noble, sacred) and Al Quddus is one of the attributes of God in Islam. It is an al-ard al-Muqaddasah (the Sacred Land, 5:21) and its surroundings are called Barakna Hawlaha (God blessed its precincts, 17:1).

- Jerusalem is the site of Isra (Muhammad’s night journey from Makkah to Jerusalem) and Mi`raj (Muhammad’s ascension to heaven). The importance of these two events for Muslims is reflected in their reverence for the two sacred places.

- Jerusalem is the third holiest city in Islam after the city of Makkah, Madina.

- Jerusalem is the site of Isra (Muhammad’s night journey from Makkah to Jerusalem) and Mi`raj (Muhammad’s ascension to heaven). The importance of these two events for Muslims is reflected in their reverence for the two sacred places.

- Muslims believe that Jerusalem is the only place on earth where God brought together all prophets during Muhammad’s ascension to heaven and they prayed together and Muhammad was asked to lead them in prayers.

- Al Aqsa in Jerusalem and the Ka`ba in Makkah are the only two mosques mentioned by name in the Qur’an.

- Some great companions of prophet Muhammad are buried in Jerusalem

- Most significant is the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem, a great monument of Muslim architecture.

Note: Translation of the Qur’anic verses and many of the Hadith translation with references were taken from Islamicity.com; some translations of and references to the Hadith were taken from ahadith.co.uk.

What are some of your tradition’s myths about Jerusalem?

David Arnow

Jewish

David Arnow

Jewish

As Mary notes, Judaism and Christianity share traditions that identify Jerusalem as the “navel of the earth.” Jewish and Islamic sources further claim that creation itself began with a particular stone, the “foundation stone,” located in the city. According to Jewish legend, this stone would remain the locus of critical events. It would be the site of the altar on which Abraham bound his son Isaac as a sacrifice, the rock on which he rested his head for the night when he dreamt of angels ascending and descending a ladder reaching to the heavens, and the Holy of Holies in the Temple. The Dome of the Rock stands above that place today.

Given its mythic pride of place in the order of creation, it’s not surprising that myth wraps Jerusalem in visions of perfection. “No man ever met with an accident in Jerusalem; No fire ever broke out in Jerusalem; No structures ever collapsed in Jerusalem.”

The reality of course, could not have been more different. Warring empires repeatedly sacked and burnt Jerusalem, and slaughtered its residents in droves. Unsustainable tension between the realities and visions of perfection probably gave rise to legends about the existence of two Jerusalems, one the earthly city, the other in heaven. The origins of this myth reach back to a midrashic reading of a verse from Psalm 122, a psalm devoted to the pilgrims’ visit to the holy city. Psalms 122:3 speaks of “Jerusalem built up, a city knit together.” The phrase “knit together,” (shechubra la yachdav) which likely referred to the city’s fortifications* or its surrounding wall, supplied midrashically inclined readers with the basis for a vision of two distinct cities. According to the Talmud, God will remain in exile from the heavenly Jerusalem until the earthly city is rebuilt.*

Myth has likewise given rise to the popular meaning ascribed to the city’s name—“ir shalom,” “city of peace.” (Modern scholarship suggests the more likely origin is ur Shulmanu, the city of Shulmanu, city of the West Semitic god of that name.)* A fifth-century midrash tells a story about Jerusalem’s name that remains poignant today given the conflicts surrounding the city. This legend recounts that Abraham referred to the city as “yireh” (as in Genesis 22:14, “Adonai yireh,” “God has vision”). But Shem (strictly according to midrash) called it Shalem (as in Genesis 14:18, “King Melchizedek of Salem,” “Salem,” “Shalem” in Hebrew, meaning “peace”). God said, if I call the city yireh, one righteous man will be offended. If I call it Salem, the other righteous man will be offended. Therefore I will use both names, “Yirehshalem,” “He will see peace.”*

Mary C. Boys

Christian

Mary C. Boys

Christian

As did Judaism, Christianity viewed Jerusalem as the axis mundi, the navel of the earth. Because of its rivalry with Judaism, however, early Christianity added a new layer to this symbolism. Texts in Ezekiel (5:5 and 38:12) seem to have first given rise to this symbolism, which was embellished in later writings, such the passage in the pseudepigraphal book, Jubilees 8:19: “Mount Zion was in the midst of the navel of the earth.”* Jerusalem as the center of the earth also occurs in rabbinic literature.* Christian teachers added a new dimension, connecting it to Christ. For example, Cyril, bishop of Jerusalem 349-384, preached about how Christ stretched out his hands on the cross to embrace “the ends of the world, for this Golgotha [the hill on which Jesus was crucified] is the very center of the earth.” Sophronius, patriarch of Jerusalem when Muslims conquered that city in the seventh century, wrote in one of his poems:

Let me walk your pavements

And go inside the Anastasis*

Where the King of all rose again

Trampling down the power of death

And as I venerate that worthy Tomb,

… .Prostrate I will kiss the navel point of the earth, that divine Rock

In which was fixed the wood

Which undid the curse of the tree

How great your glory, noble Rock, in which was fixed

The Cross, the Redemption of mankind.*

But more than rivalry with Judaism was at play in Christian attachment to the land. It was a living link to Jesus and his earliest followers: “If there were no places that could be seen and touched, the claim that God had entered human history could become a chimera.”*

Muhammad Shafiq

Muslim

Muhammad Shafiq

Muslim

Muhammad’s night journey and ascension into heaven (al-lsra’ and al Mi’raj) are significant in Muslim tradition. According to Muslim tradition, Muhammad was transported one night on a winged mule (Burraq) from Mecca (Makkah) to Jerusalem. The archangel Gabriel was riding the mule. According to some narrations, he was welcomed at Jerusalem by all the prophets, including Abraham, Moses and Jesus (peace be upon all of them). After meeting them, Gabriel asked Muhammad to lead the prophets in prayers. Afterwards, Muhammad was brought to the place where the Dome of the Rock is built and ascended to heaven accompanied by Gabriel.

It is said that the top portion of the Rock ascended with Muhammad until he reached heaven and then it returned to its place. Today it sits on the top of the rock like a canopy. There is a mark on the top of the Rock that is said to be Muhammad’s footprint. There is also is a mark of Abraham’s feet on a stone on which, according to Muslim tradition, he stood to build the Ka`ba — the House of God at Makkah. In his ascension, Muhammad passed through the seven heavens where he encountered earlier prophets.

During his ascension to heaven, Muhammad received the command to establish five daily prayers (Salat) that all Muslims must perform. It is said that God first commanded him to worship 50 times a day. When Moses heard about it, he persuaded Muhammad to go back to God to reduce the number. Because of Muhammad’s plea, God reduced it to 10 times. Moses insisted that also was too many and said he must go back to God to further reduce the number. Again at Muhammad’s request, God reduced it to five times a day. He said whoever would pray five times daily would be rewarded as though the person had prayed 50 times. Moses told Muhammad that even five times were too many because his people found it hard to pray just three times a day. Muhammad responded that he hoped the community would fulfill its obligation of five times.

The story of Isra and Miraj is full of wonderful signs and symbols. Muslim scholars, Sufis (mystics) and poets have interpreted it in deep, meaningful ways. There is, however, one essential point: It is an example of every Muslim’s deep devotion and spiritual connection with Jerusalem.

The whole journey happened in a portion of a night, although some critics argue Muhammad’s journey was spiritual and not physical. Like Christians and Muslims who believe that Jesus physically ascended to heaven, most Muslims believe in Muhammad’s physical ascension to the heavens on that night.